Enhancing the Evaluation of Unaccredited Institutions: Using the CIPP Model

By Laura Vieth, Deputy Director, Georgia Nonpublic Postsecondary Education Commission

Introduction

Assessing an institution is challenging. Evaluations are expected to be accurate, thorough, and completed in a timely manner. At regulatory state agencies, the evaluators are tasked with gathering and reviewing information as an outsider. This includes gaining an understanding of institutional operations and educational programming and then applying this knowledge to review and measure the institution’s processes against agency rules and regulations. Given the complexity of higher education evaluation, with competing internal interests and layers of external regulatory oversight, it is important to periodically examine the practice of institutional evaluation for purposes of compliance.

One area often overlooked within the educational institutional evaluation field is the assessments of unaccredited postsecondary institutions. This group of institutions is unique. They are not recognized nor regulated by a federal agency because they were specifically excluded from the Higher Education Act of 1965 and its amendments. Because of this, unaccredited institutions are ineligible for federal student aid and thus are often not on the radar for regulators and lawmakers. Although excepted from federal laws, unaccredited postsecondary institutions can operate in individual states. This means any regulatory guidelines are at the discretion of state oversight, including the development of an evaluation process.

In an effort to develop improved processes for evaluations of unaccredited postsecondary institutions, a regulatory state agency recently completed a research study to explore, test, and implement appropriate measures for use in assessment. This was achieved through a utilization of the action research methodology and the Stufflebeam (1971) Context Input Process Product (CIPP) Model.

This article proposes that the CIPP Model is a useful tool for expanding and enhancing the evaluation process of unaccredited postsecondary institutions.

Additionally, the model’s application has the potential to strengthen accountability relationships, encourage a culture of improvement at regulatory state agencies, and prioritize the role of perception in quality enhancement efforts. Moreover, the challenges associated with the evaluation of unaccredited institutions, insights into the supporting structures of this particular study, and a presentation of preliminary findings are discussed to provide a framework for further exploration.

Why prioritize the evaluation of unaccredited institutions?

States vary in the guidelines applied to unaccredited institutions. For example, in the state for this study, unaccredited institutions can offer certificate through doctoral level programming. Historically, the regulatory state agency (RSA) had not identified reasons for distinguishing separate evaluations for accreditated and unaccredited institutions. However, this perspective shifted in 2013 when a state audit proposed that the agency should be collecting and reporting outcome data such as graduation, completion, and placement rates, associated with all authorized programming. As background, the United States Department of Education (USDOE) requires this information annually from accredited institutions in order to maintain eligibility for federal financial aid. Additionally, this public information is available from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System website, published by the National Center for Education Statistics of the USDOE. Prior to the 2013 audit report, the agency had directed outcome data inquiries to this site. This process was considered sufficient since the majority of the authorized institutions were accredited. Furthermore, these institutions generated the most questions due to the large numbers of students enrolled and the amount of federal financial student aid funds disbursed among them. With regards to unaccredited institutions, this outcome data was not reported to the RSA.

The 2015 final audit report, and resulting internal discussion regarding methods for determining educational and fiscal stability illuminated a paucity of data concerning the agency’s efforts to investigate the evolution of its institutional evaluation process. Auditors criticized the methods which were in practice since the inception of the RSA. Typically, the methods were only modified in response to external requirements.

Furthermore, the limited number of change projects was affected greatly by influences that were outside of the control of the agency.

These included factors such as insufficient budgets (for additional staffing and technological upgrades) and conformance to binding legal codes.

Fortunately, recent years have seen an increase in RSA budget for and attention to change initiatives, including the development of a new online record keeping database, electronic application portal, and upgraded website. New enhanced information technology systems now in use at the agency have allowed for easier access to data. Additionally, the online database facilitates the recording of more accurate and consistent information throughout multiple sources (i.e., website, internal institutional records). These upgrades have also improved the agency’s capabilities for comparing data, running reports for specific institutional components (i.e., programs, locations, accreditation status), and streamlining the application workflows. While the outdated internal structures of the past were potentially insufficient to support this study, those currently in place have effectively supported the agency as it sought to investigate, develop, and implement improved assessment measures.

The research study

The purpose of this action research study was for a regulatory state agency (RSA) to explore, test, and implement appropriate measures for use in the evaluation of unaccredited institutions using Stufflebeam’s Context Input Process Product (CIPP) Model. This effort was achieved over a twelve-month period and was guided by the following research questions:

- What is learned by an action research team in a regulatory state agency system as a result of applying accountability approaches in the evaluation of unaccredited postsecondary institutions?

- What cultural shifts are necessary to accommodate the implementation of new evaluation processes?

The methodological nature of the study is due in part to the fact that the lead researcher was completing the project as part of a Doctorate of Education program. In addition to a research team, comprised of agency staff, and agency leadership, the study was continually reviewed and assessed by a university dissertation committee. This ensured regular attention to record keeping, data collection, ongoing analysis, and relevant qualitative research norms such as an attention validity and trustworthiness.

The context: A regulatory state agency

The context of the study dictated the setting for the project. The RSA served as the immediate environment for the project while the macro setting, the state and national higher education regulatory environment, influenced the study in terms of evaluation trends and potential impact of oversight. On the state level, oversight of postsecondary education is relegated to three state entities; 1. Public, state colleges and universities, 2. Public, state technical colleges, and 3. All private educational institutions. The agency responsible for private educational institutions, the final group, is the RSA which provided the micro setting for this research project. It is a nonpartisan state agency responsible for the regulation of private postsecondary institutions within the state as well as for all postsecondary institutions from out of state that choose to be physically present, with either locations, active recruiters, advertisements, or online offerings to state residents. The mission of the agency is to ensure that authorized institutions are providing sufficient education while also maintaining financial stability. As a result, the agency is tasked with assessing the programs, staff, facilities, finances, policies, publications and records of all private certificate and degree-granting institutions. The RSA also has a vision to promote quality and improvement. This study directly aligns with both these goals as the research sought to enhance evaluation, thus improving the agency procedures and operation.

The sample: Unaccredited institutions

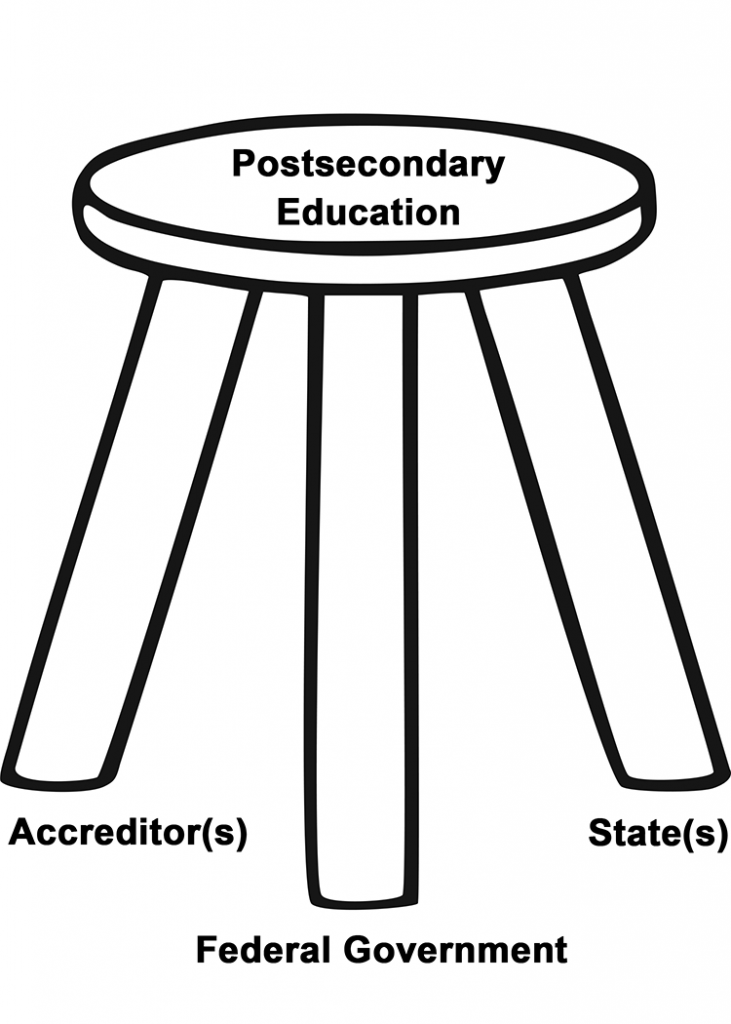

In comparison to accredited postsecondary institutions, unaccredited institutions are underregulated. Accredited institutions must first be authorized in their home state prior to seeking accreditation. Following state approval, they must submit to the accreditation application and approval processes. Subsequent to accreditation approval, most institutions then seek access to federal student aid. This requires another layer of compliance and oversight which is supported by the well known higher education triad composed of state, accreditor, and USDOE regulation. Figure 1 illustrates the “The Triad,” also known as the three-legged stool, which refers to the current system of regulation guiding the oversight of accredited postsecondary institutions.

Figure 1. The Regulatory Triad

Unaccredited institutions, alternatively, are typically only responsible for rules and governance of the state in which they operate. In order to address this limited oversight, this study focused solely on unaccredited postsecondary institutions. For purposes of the study, unaccredited is defined as lacking accreditation by a USDOE recognized accrediting body. Size of the institution in terms of number of students or amount of tuition and fees collected, programmatic offerings including degree level, and history with the RSA all had no effect on whether or not each was included in the institutional sample. Lack of accreditation along with authorization oversight were the factors used to distinguish the sample population. In March 2016, (beginning of the study), there were 123 unaccredited institutions authorization by the RSA. Ten of these offered degree programs only, in comparison to offering only certificate programs or offering both certificate and degree programs. The group varied by programmatic offerings with the key areas of instruction being allied health (45.5 percent), IT (13.8 percent), and dental health (6.5 percent). The percentages indicated identify the portion of the sample represented.

The research methodology

Action research guided the study. This research methodology centralizes around the concept that situational conditions create a unique environment that determines a multitude of research factors including, but not limited to, access, content, perspective as well as available options for development (Stringer, 2014). Additionally, in action research, insider change initiation is critical to the change process. For example, this methodology requires the researcher be in the midst of an issue to appropriately study it. This immersion allows the researcher to maneuver within an environment that has personal meaning and value.

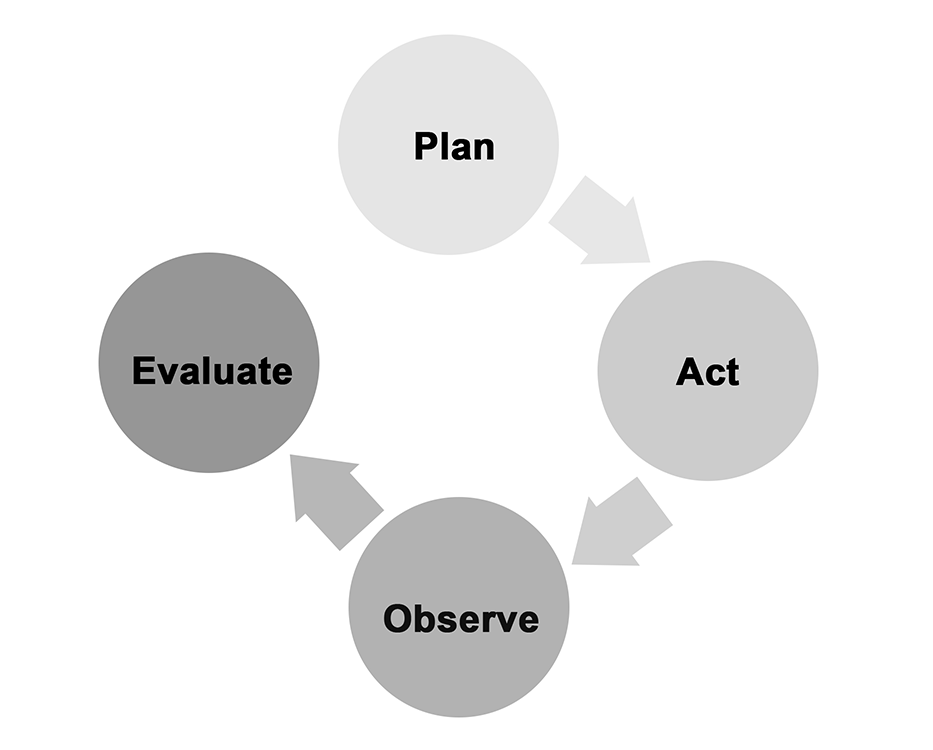

In addition to a first-person perspective, action researcher encourages collaboration with stakeholders that have a similar personal connection to the problem. This collaboration creates the momentum to proceed through the cycles of constructing, planning action, taking action, and evaluating action to initiate change. Figure 2 provides a visual for one cycle of the action research process.

Figure 2: Action Research Cycle

Through iterative action, the completion of multiple sequences of the action research cycles, a research team is able to dive deeper into the solution process. Furthermore, any alterations made are enacted through a process of experimentation that is unique to the problem and the group. As such, this process generates findings that are context specific, rather than generalizable, one-size-fits-all-solutions.

The research team

The participants in this study included the action research team members and the agency staff. Research team members participated voluntarily in addition to their official job responsibilities. The one exception to the dual roles of the members was a retired agency director. While he was no longer responsible for day-to-day tasks, he willingly participated to help provide additional insight into the problem as well as to share in the experimentation process. The RSA staff provided comment on research team propositions and actions as part of their roles as employees. This was achieved primarily through office meeting discussion, where information was shared regarding any interventions affecting institutions and/or agency processes was shared. It is important to note that transparency was maintained with the RSA staff throughout the project. As a result, in addition to formal meetings, there was ongoing informal communication with agency colleagues during all stages of the study.

The model

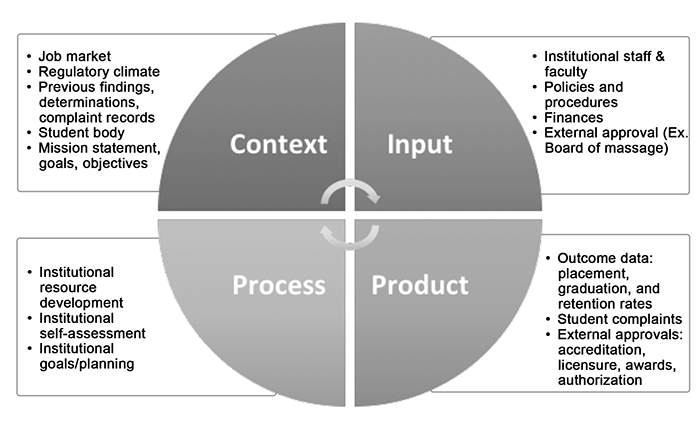

The Context Input Process Product (CIPP) Model, created by Daniel Stufflebeam in 1971, is a framework for implementing a systems theory guided program evaluation. This evaluation structure seeks to offer a platform for answering four questions: “What should we do? How should we do it? Are we doing it correctly? and Did it work?” (Stufflebeam, 1971, p. 5).

Its purpose is to monitor evaluation and assessment in a manner that is comprehensive and inclusive, as review is encouraged by both the evaluated and the evaluators. Stufflebeam (2001) argues that this inclusion increases the professionalism of the evaluation.

Additionally, the CIPP model promotes stratified assessment of the whole system, as noted by Zhang, Zeller, Griffith, Metcalf, Williams, Shea, & Misulis (2011), who believe it provides a “systematic comprehensive guiding framework” (p. 62). The four areas of focus are: context (needs assessment), input (planning), process (monitoring), and products (measuring, interpreting, judging, and interpretation).

With the aim of improving accountability through the application of the model, the research team developed a RSA specific CIPP model (Figure 3). Throughout the study, this model acted as a planning and monitoring tool. The model was referred to for potential future actions as well as utilized in assessing previous interventions. Furthermore, it provided an image to represent the evolved holistic view of the institutional evaluation process.

Figure 3: RSA CIPP Model

Findings

Private postsecondary institutions can be categorized into multiple areas (ex. cosmetology, online, certificate-granting, allied health, and IT); however, specific to the areas of regulation and evaluation, accreditation status is an important distinction. Institutional accreditation affects funding, most critically due to federal student aid access. In turn, funding impacts the institution’s ability to operate, including purchasing suitable equipment, employing adequate staff, and enforcing complex and time-consuming regulatory policies.

Terminology issues

An initial finding was a misunderstanding by some unaccredited institutions of the difference between the terms “authorization” and “accreditation” and the required procedures to earn each status. While the RSA regularly encounters institutions proclaiming their “accreditation,” erroneously labeling the agency’s authorization status, this confusion persisted throughout the study. This misnomer presented itself in emails with the agency, in institutional publications, as well as in conversation between agency staff and institutional representatives. To address the confusion, institutions were notified that this project was focused on unaccredited institutions. Additionally, this was communicated in person during an information session addressing the study and its first round of interventions. Furthermore, the distinction between accreditation and authorization was presented in a new student disclosure form.

In addition to the inaccurate interchanging of the terms “accreditation” and “authorization,” the research team witnessed a discomfort of unaccredited institutions with the agency labeling of this group as “unaccredited.” This was mediated by the RSA, in part, through a compromise which modified a disclosure form’s language to indicate that while the institution was authorized by the state, it “is not accredited by a US-based accrediting association recognized by the United States Secretary of Education.” The explicit acknowledgement of state approval appeared to soften the negative reaction to being identified as somehow less than or bad based on a lack of accreditation.

Stratified processes

A central finding arising from the study is that accredited and unaccredited students vary greatly in terms of institutional resources. This is especially so concerning the human resources necessary to collect, report, and respond to requests for information. Weaknesses in this area may limit the ability of the RSA to complete a thorough and productive evaluation of an unaccredited institution. Appropriate institutional representative experience and knowledge impacts evaluation through its effect on an institution’s ability to comply with regulations.

Specific to outcome data collection and reporting, one RSA survey indicated that 62 percent of the respondents worked at institutions that currently did not report outcome data to any regulatory body.

Inexperience of this nature impacts the ease at which institutions can accommodate changes in RSA evaluation practices, such as those encouraged as part of this study. A stratified state authorization process, with delineations for accredited and unaccredited institutions, allows for a more customized evaluation and assessment that may better fit the needs of unaccredited institutions. Furthermore, this practice has the potential to benefit the RSA and the institutions by empowering both parties to utilize regulations and mandated evaluations to encourage quality improvement.

Consumer protection

In addition to the impact of accreditation on institutional operation, through the likelihood of sufficient resources, the research team also found that it impacts the RSA’s ability to address consumer protection. Lacking accreditation often means less information is available to consumers, as is the case in the state of the agency. Taking action to understand unaccredited institutions, in this case, completed in part through additional data collection, can assist the RSA to better recognize problem areas as well as those generally in need of improvement. This identification can help support and protect consumers, a responsibility regularly assigned to state agencies. A progressive critique, one intended to support improvement, is likely to encourage institutional development. This, in turn, serves students, future employers and their clients, as well as the overall state commerce.

Benefits of the CIPP Model and action research methodology

The CIPP Model (Stufflebeam, 1971), focused on context, input, process, and product, was chosen to guide this study due to its comprehensive holistic approach to evaluation. The research team found the CIPP Model proved a useful tool for expanding and enhancing the evaluation process. One particular benefit of the CIPP Model is its systematic nature. This allowed the RSA to analytically review existing practices utilized in the evaluation of unaccredited institutions and also to consider and test alternative and/or modified processes. Moreover, the models fit well with the action research methodology with its emphasis on iterative review, insider work, and stakeholder inclusion.

Stakeholder input was encouraged throughout the study and was found to not only improve the quality of interventions implemented by the research team but also helped to improve accountability between the RSA and the unaccredited institutions. Institutions were included in the development process and were able to see their feedback affect change. Their inclusion not only gave the agency the opportunity to share the background on the project but also the logic behind the changes, rather than simply enforcing mandates.

This promoted a shift in the RSA culture towards a greater effort to support institutions. As one RSA staff person stated, institutions were not “sent up the stream without a paddle.”

Communication with institutions also served to assist the RSA to identify opportunities to encourage institutional progress rather than place judgment in the form of approval or denial. By analyzing compliance for improvement, a regulatory state agency can encourage a higher quality of education as well as improve relationships with institutions.

Mirrored quality improvement

In addition to the study impacting the agency’s perception of an institution’s ability to improve, it also illuminated the ability of the agency to improve itself. Because the CIPP Model and action research methodology allowed the study to be implemented effectively, the RSA was empowered to dig deeper and to expand its efforts to progress. This success has created an agency environment where process improvement efforts were noted by one research team member to be “ kind of an expectation now … To work towards improvements and to assess where we are, and be critical of it and how to make it better, as opposed to just going with the norm because that’s how it’s just been.” By including the agency under the evaluative lens used to examine institutions, it was able to identify internal weaknesses, and staff have been eager to improve and/or correct these areas. Overall, the project was a success. The CIPP Model empowered the RSA to tackle a difficult and complex issue which resulted in improved operations of both the institutions and the RSA itself. Most importantly, because of improved processes, the state and its students are now better served as a result of the agency’s effort to improve accountability through evaluation.

References

Stringer, E. T. (2014). Action research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Stufflebeam, D. L. (1971). The Relevance of the CIPP Evaluation Model for Educational

Accountability. Paper read at the Annual Meeting of the American Association of School Administrators. Atlantic City, NJ.

Stufflebeam, D. (2001). Evaluation models. New directions for evaluation, 2001(89), 7-98.

Zhang, G., Zeller,N., Griffith, R., Metcalf, D., Williams, J., Shea, C., & Misulis, K. (2011). Using the context, input, process, and product evaluation model (CIPP) as a comprehensive framework to guide the planning, implementation, and assessment of service-learning programs. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 15-4. p. 27.

DR. LAURA VIETH has served the Nonpublic Postsecondary Education Commission since 2011 acting as a Standards Administrator for six years and, most recently, as the agency’s Deputy Director. Prior to higher education compliance, her work focused on instruction, teaching English abroad, and completing a master’s degree in teaching. She is a recent graduate of the University of Georgia where she completed the Doctor of Education in Learning, Leadership, and Organization Development degree program. Her professional interests are focused on change management, quality improvement and effective collaboration.

Contact Information: Laura Vieth, Ed.D. // Deputy Director // Georgia Nonpublic Postsecondary Education Commission // 770-414-3306 // lauras@gnpec.org // www.gnpec.org