SARA – Twenty-three States and Counting

Written from an interview with Marshall A. Hill, Ph.D., Executive Director, National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements

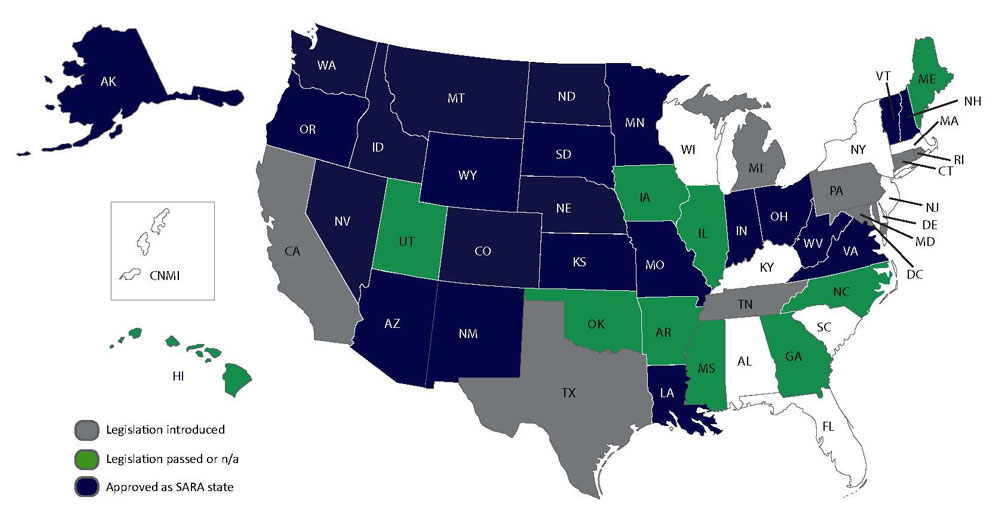

SARA Member States

Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, South Dakota, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia and Wyoming

Executive Director of the National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements, Marshal Hill believes that distance education can help improve America’s educational system once the inefficiencies of the current state regulatory system are codified across the board.

“We have significant educational attainment gaps in our country,” he notes. “I am in my mid-60s, part of a group of people, Americans, who are the best educated in the world. American students who are 18–34, however, are the not best-educated 18–34-year-olds in the world. They are not second, not fifth, nor even 10th – they are 13th. So, we need to make progress on post-secondary attainment. Distance education can be a part of that. Therefore, we need to do it efficiently, and we are not.”

Hill notes that regulations for higher education have become complex partly because of parochial attitudes. Within its borders, each state has developed its own rules for dealing with the enrollment of out-of-state students. “Some states have had minimal expectations; others have high regulation.”

By the fall of 2010, Hill continues, everything began to change: “The U.S. Department of Education issued a ruling, stating to all institutions that participated in the Federal Title IV programs that they needed to obey the laws of the states in which they enrolled students. Second, when [the DOE] audits you, [they will] check that you are in compliance with all the other states’ laws. That proposed rule got a great deal of attention. It resulted in a lawsuit, which had the rule thrown out.

“I had been on the Negotiated Rule-Making panel that tried to deal with this issue,” he continued. “The DOE should not have needed to remind institutions that they needed to abide by state laws. The Department wanted the states to step up and help regulate what they saw as a problematic area.”

“The courts said that the Department had the authority to make such a rule, but that their process for promulgating it did not meet the Department’s own stated policies. So, they tossed it out.

“But the basic issue [they make] about state law — meaning that an institution in one state needs to determine what the other states’ rules and laws are and abide by them — has been around forever.”

While that is understandable legally, it makes for institutional chaos for students and schools. In sum, he adds,

“what we have now is that a couple of thousand institutions that enroll students in states other than their own and teach them through distance education have to deal directly with [rules in] 54 states and territories.”

SARA was developed to come up with an alternative to having every institution contact 54 states and territories to find out what their rules were and what the institution needed to do and so forth and so on.

For career educational institutions with multiple campuses and distance learning programs, SARA has developed a uniform set of “standards, policies and requirements” for all states. All member institutions will need to conform to these standards and policies, including fiduciary and educational regulations.

The upside for career education institutions is that a uniform set of rules will supersede the hodgepodge of rules that can vary from state to state

The founding of SARA: the backstory

Executive director Hill has been involved in the development of SARA from the git-go, and took time to trace its founding.

“A group called the President’s Forum, which is an organization for institutions and organizations that do a lot of distance education, sought funding from the Lumina Foundation to convene a group of people to discuss the issues. They were mainly trying to identify barriers to the expansion of online education. They found that obtaining state authorization was one of the biggest hurdles that institutions faced.

“The Forum reported back to Lumina,” he continued, “asking for money to develop an alternative. The Foundation, in conjunction with the Council of State Governments (CSG), made an additional award to work on the issue.

“The idea was to develop a state compact, a set of laws that every state that chose to could adopt. There are lots of state compacts. They are the reason we do not have to have different driver’s licenses in every state.

“The President’s Forum and the Council of State Governments (CSG) convened 11 experts as a drafting team to discuss the issue, to think about solutions, and to draft model legislation. I was on that group, too. We worked for four or five months and came out with a first-draft report.”

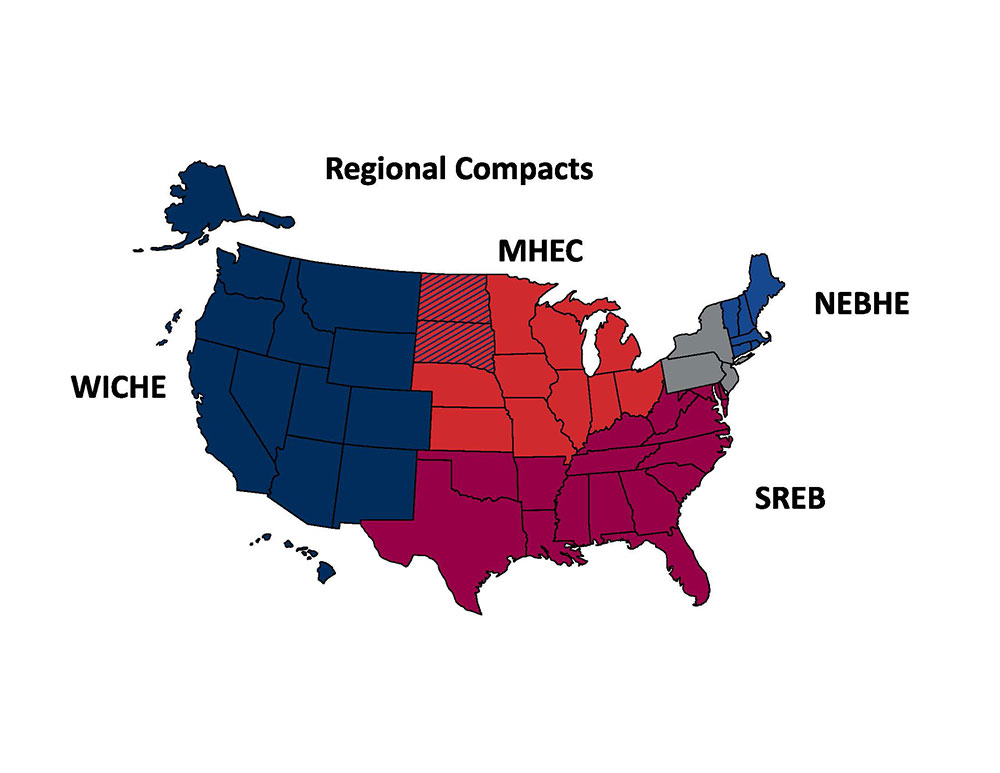

Hill notes that there were criticisms, but the four regional education compacts, all of them of long standing, wanted to be involved with the project. Negotiations were challenging, but ultimately successful. The four compacts and a national, coordinating entity now are implementing the SARA initiative.

Hill noted the challenge of coordinating issues across four regions, but says, “I am convinced that joining forces was absolutely the right thing to do. We certainly would not have been as far along as we are today had we not been able to build on the reputation and the relationships that the regional compacts have with the various states that make up their membership.”

A meeting of the minds

Hill has been a lightning rod for establishing standards for authorization. He points to meetings that kicked off in 2010 as the launch pad for what is today SARA.

A consortium of organizations that valued coordination of state post-secondary educational standards came together to establish a voluntary interstate compact on state educational reciprocity. The organizations included the U.S. Department of Education, the Council of State Governments (CSG), the Association of Public and Land-Grant institutions, the Lumina Foundation, the Gates Foundation, the President’s Forum, which is an organization for distance education institutions, and four regional educational organizations. After many meetings and much discussion, and with additional funding from the Lumina Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, they succeeded in 2013. SARA was born, and Marshall Hill was named its executive director.

SARA was established and ready to invite the first states to join by January 2014. As of May 13, 2015, 23 states have joined; several additional states are expected to join by early summer. As a voluntary agreement among the states and U.S. territories that opt to join in, SARA is setting “comparable” national standards for post-secondary distance-education courses and programs among the states.

SARA is being implemented by the four existing regional compacts: the Midwestern Higher Education Compact (MHEC); the New England Board of Higher Education (NEBHE); the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB); and the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE).

Once a state has joined, eligible institutions in the state can choose to participate. Membership is open, notes Hill: “Any degree-granting institution based in the United States… holding accreditation from an accrediting association recognized by the U.S. Secretary of Education, is eligible to apply to its home state to participate in SARA if that state is a SARA member.” SARA institutions must agree to abide by common standards, commit to helping resolve student complaints, and pay an annual fee.

The process for SARA

Executive Director Hill provides a summary of the SARA process for distance learning institutions.

“A state decides to join SARA. It invites its institutions. The institutions apply through a standardized process. The institutions then pay a fee to SARA. We keep a portion of those fees for our own support and allocate the balance to the four regional educational compacts that are doing much of the work.

“Once an institution is approved, it can offer its courses and programs in any other SARA state without having to go through the application process — licensing, authorization, or whatever the state calls it — and without having to pay fees to those states.”

“However, because SARA is an agreement between states, if your state is not participating, your institution cannot join on its own.”

Accreditation

“Most accreditors expect to be notified about an institution’s expansion into different forms of online learning or instruction,” says Hill. “SARA does not remove the need for that.”

“We do not affect much in the relationship between an institution and its accreditor,” he said. “We do use certain things that accreditors use. The most obvious is a set of Best Practices that the Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions (CRAC) adopted several years ago, and which had been around in essentially the same form for at least 20 years. They built them into their accreditation standards. SARA builds on those standards and puts them front-and-center in the requirements for an institution to join SARA.

“For example, the president or provost of an institution that wants to join SARA must sign off, saying, ‘My institution meets these guidelines and will continue to meet them.’ These are currently built into all the regional accrediting bodies’ Criteria and Standards rules.

The process for college participation in SARA

According to Hill, signing up for SARA membership is a straightforward, ‘step-by-step’ process for states and institutions.

Once a state decides to participate, it applies to its regional education compact SARA office (MHEC, NEBHE, SREB, and WICHE) for permission to join. If the state has been approved, SARA-eligible institutions can choose to participate.

Hill notes that there is a profile for schools wanting to become members of SARA:

- The school must be a degree-granting institution that offers an associate’s degree or above

- The school must be accredited by an accrediting body recognized by the U.S. Department of Education

- If the school is a non-public institution, it must have a Federal Financial Responsibility Index score of 1.5 or above for automatic admission. If it has a score of 1.0 to 1.5, it has the option to petition its state SARA entity that it is financially stable enough to participate in SARA.

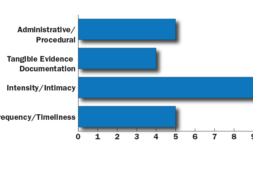

The SARA resolution process for student complaints

SARA also has a complaints process for students.

As formulated, the SARA process will root out false advertising and corruption before it has time to fester, ultimately improving the reputation of distance-learning institutions.

Hill notes, “We have a good complaints process for students.” He offers an imaginary example using two real SARA member states: “A student in, say, Colorado, is taking an online course from another SARA member, say, the University of A in Nebraska. That is also a SARA institution in a SARA state.

“Let us say as a demonstration, that the student feels he or she has been mistreated by the University of A. If his complaint is about a grade or a violation of student conduct rules, those kinds of complaints get resolved at the institution. The student proceeds through the full student complaint resolution process at his or her home institution.

“If, however, his or her complaint is about something other than grades or conduct, for example, it involves the school’s failure to provide advertised offerings, that makes it a SARA issue.”

Hill cites as an example a student saying, “They told me that there would be a lot of resource material to review during my online studies, but they never provided it.” Or, “They told me that they would abide by their posted tuition refund policies, but they did not.”

“Then,” Hill says, “the student could appeal to the state SARA agency — to the agency in Nebraska that is doing the SARA work — and make his or her case to that entity. That entity would then resolve the student’s complaint.”

While Hill is a strong advocate for distance learning, he takes student complaints seriously. “We are going to publish the number of complaints that have been appealed against SARA institutions,” he says. “This is not every complaint that has been made, because the majority of them are resolved at the institutions, but the complaints that are appealed to the state SARA entities.

“We will collect that information quarterly and post it on our website. Actually, we are collecting it right now,” said Hill. “They will report the names of the institutions participating in SARA, the number of appealed complaints, and how those appeals were resolved: In favor of the student, in favor of the institution, resolved by mutual agreement, or we have not yet resolved this.” (The first cycle of those reports is already on the NC-SARA website.)

Hill also notes another place to lodge serious complaints is the state’s attorney general’s office. He adds, “One other thing to mention regards allegations that students might make about fraud or misrepresentation and so forth… In any state, a SARA member or not, students can always appeal to the state attorney general. Attorneys general apply general laws of consumer protection, and they can deal with those allegations.”

SARA after 18 months: growing steadily

“As of May 13,” executive director Hill says, “23 states have fully signed on to SARA. My estimate is that by the end of 2015, we will have around 35 states and be building beyond that.

“We are doing well,” he says. “We have 260-some distance learning and educational institutions signed up. Most are from the first 10 or so states to join. A number of other states have passed legislation [to join], too. They are working through the development of rules. We also have legislation pending around the country in quite a few states.”

“Frankly,” Hill says, “we are considerably ahead of where those of us who started working on this issue in 2010 thought we would be. We just began inviting states to participate last February. Here we are now with 23! We imagined we would be very successful if we could enroll 10 states in the first year. Instead, we have doubled that.”

Hill reiterates that SARA works by a set of carefully elaborated ground rules. It is a voluntary agreement between states, he emphasizes, “on how to operate their dealings with out-of-state institutions that want to offer distance education. It is not by whatever means they had in place before joining SARA, but by SARA provisions. So everybody agrees on this set of ground rules.

“It is like everybody agrees on the size the basketball court is going to be and the height to the basket. You are not going to have to play with different size courts and different type baskets, depending upon on what state that you are going into.”

Some hurdles will remain for schools

Once the standards and policies are established, the continuing challenge for distance learning programs will come under the rubric of what is known as ‘physical presence.’

As SARA executive director Hill explains, ‘Physical presence’ is the term of art that sets out a set of points or actions; if you trip those, the state says we are going to regulate you. SARA does not remove all those trip points.

“For example, let us say you are Indiana University at Bloomington, which is a SARA institution. If IU wants to offer its courses and programs in another SARA state via online instruction, it just proceeds. That is all it has to do. It will not have to contact Colorado, Oregon, Washington, and so forth.

“If, however, IU wanted to build a campus in Missouri, or lease space to teach students there, they would still have to deal with the state laws of Missouri. What they do not have to do is go through all the regulations which do not represent physical presence.”

Another remaining hurdle exists for institutions offering distance education programs aiming toward professional licensure in fields such as nursing and allied health, psychology, or teaching.

For those and other licensed professions, institutions will still need to abide by the expectations and rules of state boards overseeing those professions in all states in which they are enrolling students.

How to get your state to join SARA

Hill notes that the process of getting a state to join SARA is relatively easy, citing the state of Nebraska, where he formerly worked. “We got a bill passed in Nebraska. It said that in addition to the other enumerated duties of the Nebraska Coordinating Commission, the Commission may enter into an Interstate Reciprocity Agreement for Post-Secondary Distance Education on behalf of the state. It may administer that program and may charge fees to any Nebraska institutions that choose to participate, so long as those fees do not exceed the amounts needed to recover costs. That was it. All sectors of Nebraska higher education supported the bill”

“Many other states have done that,” Hill notes, adding, “There are a few states that do not have to change their laws. Alaska is my favorite example. Tucked into the statutory language for the Alaska Board of Regents is a sentence or two saying something like: “To further the goals of this chapter, the Board may enter into reciprocity agreements with other states. The Alaska Attorney General determined that, that gave them sufficient legal authority to enter into this agreement and they did.”

How to learn more about SARA

Hill urges educators, particularly those in distance learning programs, to follow SARA’s progress. The SARA website, www.nc-sara.org, offers several sources:

- The SARA website has a signup for e-newsletters

- SARA schools are easily found through the website map of the U.S. – click on a state and immediately see a list of the SARA institutions within that state

- A SARA staff-generated document that tracks the actions of states as they consider SARA initiatives.

“Even in the states with no checkmarks,” Hill notes, “there are active discussions about participating in SARA.”

Marshall A. Hill is Executive Director of the National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements (NC-SARA), which provides a voluntary, regional approach to state oversight of postsecondary distance education. His involvement with SARA spans work with the Presidents’ Forum/ Council of State Governments drafting team, the development of SARA agreements with the country’s four regional higher education compacts, and membership on the National Commission on Regulation of Postsecondary Distance Education. Prior to assuming his NC-SARA position in August of 2013, he served as executive director of Nebraska’s Coordinating Commission for Postsecondary Education, assistant commissioner for universities and health‐related institutions at the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, and as a faculty member for 17 years, conducting choirs and orchestras. Dr. Hill has served on four negotiated rule‐making panels for the U.S. Department of Education, negotiating federal rules affecting accreditation and student financial aid. Active in several regional and national organizations, during 2012-2013 he served as chair of the executive committee of the State Higher Education Executive Officers association (SHEEO). Hill earned B.A. and M.A. degrees in music from Utah State University and a Ph.D. in music education, with a minor in higher education from Florida State University.

Contact Information:Marshall A. Hill, Ph.D. // Executive Director // National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements // 3005 Center Green Drive, Suite 130 Boulder, CO 80301 // 303-541-0283 // mhill@nc-sara.org