Most Talked-About Keynote Session Asked Can We Come Together?

By Barbara A. Schmitz, written from the CECU Convention Keynote Session with Peter Cohen, President, University of Phoenix and James Grant, CEO, Universal Technical Institute

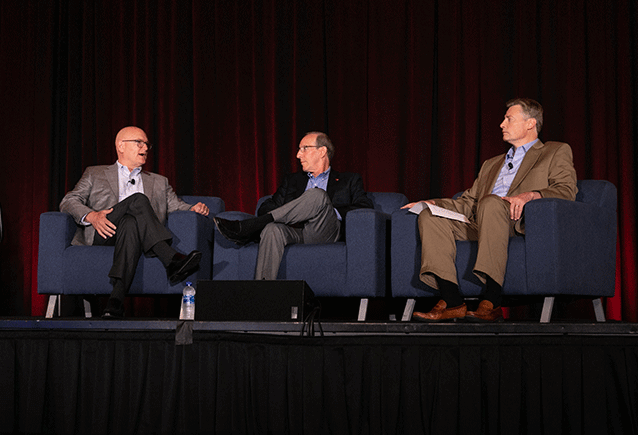

Peter Cohen, president of the University of Phoenix, defended the college’s reputation, saying it is one of the most scrutinized universities in the nation and that they are doing much to improve their reputation and serve students.

Cohen answered questions from Career Education Colleges and Universities members on what the University of Phoenix is doing to overcome the perception that it is a “bad player” in the career education sector. CECU members also asked why Cohen and Jerome Grant, CEO of Universal Technical Institute, are not members of the CECU. The two spoke on “Career Education and Distance Learning: How can we work together?” at the June CECU & CCST 2021 Career Education Convention.

Cohen said the University of Phoenix has made several changes to improve its reputation and choose to settling with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) regarding a 2012 advertising campaign about 18 months ago.

After five years and millions of documents, all the FTC found against them was a 2012 advertising campaign that the FTC said could be misleading, Cohen said.

“We so vociferously disagreed with that perception that I put those commercials on our website and they’re there today so that anybody in the general public could make their own determination of them,” he said. The advertising campaign was about “let’s get to work” and it talked about the fact that if you get a degree, you might be able to go to certain employers and potentially get an interview, he said.

However, the FTC perceived that those ads guaranteed people would get a job with the mentioned employers.

“At the end of the day, we made the business decision to settle with the FTC rather than be in court for four more years and … not be able to focus our leadership team on student success,” Cohen said. However, it turns out that once you settle with the FTC, everybody else comes looking to “check under the cover” as well, such as the Department of Education, he said.

“We have never been fined for anything,” Cohen stressed. “We’ve never been found guilty of anything. What you have is an incredibly active press and a group of people in the media who are determined to create a story where one doesn’t necessarily exist, in order to try to further their own agenda.”

Cohen said the University of Phoenix has 85 compliance and regulatory staff.

“We listen to every single phone call using automated semantic voice analysis to determine whether any enrollment adviser, any academic counselor, any financial aid person has said anything that could be misconstrued,” he said. They listen to all the calls allowed by state and follow up with those calls that could confuse anyone. Cohen said they not only meet with the staff to properly coach them to not say things that can be misconstrued, but they also call students to make sure they understood what was said.

“We are probably the most scrutinized university in the country,” he said. “And we have never had a case, at least in the last five years that I’ve been there, where we’ve been accused of anything that has been demonstrated by any regulatory body or a court as proof. But you still get that same court of public opinion.”

Cohen said all of their marketing is reviewed by a legal compliance team, first on the marketing side and then on the legal side, oftentimes with an outside FTC attorney. “No piece of marketing goes on our website, goes on air, goes on radio, without being reviewed first to make sure that everything we say is substantiated and backed up.”

Across the organization, they feel that they have put in place internal practices to ensure staff are focused on compliance compared to any other university their size, he said.

Cohen challenged the group to look at the advertising and claims of colleges such as Western Governors, Southern New Hampshire University and Arizona State University, and then compare them to the University of Phoenix. “You will find that ours are more conservative in every single aspect than anything any of them say, because nonprofits (are) not under the scrutiny that we are.”

In addition, the University of Phoenix stopped using third party affiliate marketers who might say something they don’t have control of.

“We use some content marketers over which we totally control the message,” Cohen said. “We don’t buy leads from anybody. Anybody who wants to come to the university has to come to our website and they have to register on our website. We have in place a lot of practices to make sure that we are not misconstrued by the general public.”

Using alumni to promote the school

Cohen said they also continue to have their alumni speak to legislators about their positive experiences at the University of Phoenix. Those alumni and an alumni network help politicians see them as people.

“Stories matter more than facts and stories matter more than data,” he said. “If you can tell a great story, you can win over a regulator or a politician.”

Cohen said all career education schools would benefit from mobilizing alumni to talk to legislators and policy makers, and make them see the world as it really is. He said he also meets with senators and congressmen to discuss the university’s focus and to reinforce that all career colleges want accountability with no bad actors.

“I want every student to get to graduation,” he said. “I want every student to have a good return on investment.”

Accordingly, the University of Phoenix has lowered the cost of some of its four-year bachelor’s programs to $25,000 total and master’s programs to $10,000 total.

They remain one of the largest online universities in the country, enrolling about 75,000 students.

Cohen said when the University of Phoenix went private four years ago, they really looked at what was their core value and what they were trying to accomplish with their students.

“We’ve spent the last four years doubling down on those services that will allow our students to continue to succeed and to get to graduation,” he said.

In short, they’ve built in short courses, micro-credentials and badges, realizing people need to continue to increase their skills in a society where technology is changing jobs quickly.

“And we’ve built in counseling services and coaching services and assessments to help people find the right jobs,” he said. “Finally, we’ve built in mentoring. Because when our students, typically people of color, get into the corporate world many of them have not had corporate friends before.”

Cohen said they’re able to build a social network that allows their graduates to get that promotion they need and build their network of mentoring partners.

“We have a million alumni and those million alumni are part of that mentoring network,” he said. “That’s our focus for the future, focusing on students’ needs for the life of their career, not just while they’re getting their degrees.”

The biggest impediments or threats to that vision is competition, although competition is a good thing, Cohen said. “It makes you sharper, it makes you more focused, it makes you better at what you do.”

But what most concerns Cohen about the future of the industry is the differentiation between Section 101 and Section 102 schools.

Cohen said Section 101 schools have a certain set of standards that are very broad and very easy to accommodate. But Section 102, which includes a career education school like the University of Phoenix, has a “entirely different set of standards,” he said. “They set a bar that is much higher and much more specific. And the more that the current administration tries to increase the differences between those two sectors, the more challenges there are for our sector to compete with a nonprofit sector.”

He said it doesn’t matter if you’re talking about gainful employment, the 90-10 rule or financial repayment issues. “It’s just a very unlevel playing field and I fear that it could get more unlevel,” Cohen said. “If it gets really disproportionate, I think it’s a real threat to the industry.”

Putting profits before students?

Based on his observations and discussions, CECU President and CEO Dr. Jason Altmire said there is concern about private-equity-backed schools and publicly traded schools. Those concerns revolve around putting profits before students, and of marketing and recruitment practices being led by business decisions rather than other motives.

While the University of Phoenix is currently owned by two private equity groups, Vistria and Apollo Global Management, they care more about the students than they do profits, Cohen said.

“I’ve worked with Apollo Global Management across four different education companies, and I’ve worked with the same senior partner,” Cohen said. “I can tell you unequivocally and emphatically that he cares more about student success then he does about profitability. He understands that the way you get long-term economic benefit is by serving your students well, and anybody with half an insight into how business works would recognize the only way you get long-term success is if your customer succeeds. In our case, our customers are students.”

Cohen said the idea that a private equity group would strip the assets from an education company is nonsensical.

“The only way they can create value is to grow the business, and the way you grow the business is to get more students interested in coming there because you have a great value proposition and students succeed,” he said. “I think this whole conversation around private equity being bad for education … is very misguided and very uninformed.”

In addition, Cohen said the University of Phoenix’s Board of Directors is another control in place to help ensure student success.

“We have a board of 11 members, and six of those members have no economic interest in the university,” he said. “They have the majority vote on everything we do.”

But Altmire said there have been examples of schools encouraging students to apply in inappropriate ways. Cohen acknowledged that was true.

“As a public company with quarterly earnings, they probably got overly aggressive about enrolling students…” Cohen said. But his responsibility as the CEO is to make sure that their school focuses on the most important thing, which is that students are graduating.

“The best way for me to make long-term earnings is to have my students succeed,” Cohen said. “I personally will not be driven by quarterly earnings or by quarterly metrics. And many of my public competitors, they have stopped talking about new student enrollment on a quarterly basis … for some of those same reasons.”

Grant said as CEO of UTI, a publicly traded company, he at first assumed that his Board would want to know everything about how he was improving the economics of their business. But that hasn’t been the case.

For instance, when the Board asked for an update about the blended learning model UTI adopted largely due to the pandemic and which about 50% will stay online permanently, Grant said he thought the Board wanted to understand the economic benefits of moving to larger student-teacher ratios online. But instead they wanted to know about things like student satisfaction, and if students felt they were getting the same education, he said.

“They believe that solving these big problems in education leads to the profits, and that the focus on the profits will not solve the big problems,” Grant said.

Why not join CECU?

Dr. Art Keiser, chancellor of Keiser University, questioned Cohen and Grant why the biggest organizations, the publicly trained companies and venture capital firms, don’t participate and join CECU.

“Today’s University of Phoenix understands that an industry divided does not serve either party well and there is a need to work together or hang separately,” he said. Cohen said they have worked closely with the government affairs team at CECU behind the scenes. “So it’s not that we’re totally misaligned,” he said, “but I think we could be further aligned if we were directly related to CECU.”

Grant said even though UTI is not a CECU member, they still do collaborate often and are a strong supporter of many of CECU activities.

“Although we’re not currently members, we’ve been what we believe to be a strong supporter for the many things that serve both of us,” Grant said. “I think it is time to come together. To what degree we come together is something that still is open.”

Both Cohen and Grant said there is disincentive for large schools like themselves to join due to CECU’s dues structure. CECU calculates the price of dues based on a school’s combined gross tuition revenue.

Brad Kuykendall, CEO of Western Technical College and a CECU chairman of the board, asked if they would be interested in becoming CECU members, if dues and voting rights were worked out proportionately. Cohen and Grant said yes.

Cohen said dues should be capped at an amount that is reasonable, and that they should not be given any more voice than any other school.

“But when it comes down to economics like that, there are bridges that can be formed,” Grant said. “I do think we need to work together, whether we are together as CECU or whether we are together just as a group of people trying to do the same thing. This is a time for us to work more closely together.”

Keiser said he feels it is critical that the schools “sing with one voice” and go collectively to the Hill.

“We’ve lost the political war because we are so fragmented,” Keiser said. “Until we pull it together, it is going to be very difficult, especially in this environment, to be able to get our message across to the left.”

Getting employers involved

Mikhail Shneyder, CEO of Nightingale College and a CECU board member, questioned how employers can be involved in advocacy and help schools change the narrative.

Grant said they make sure that when a member of Congress or Senate tours one of their campuses, they do so at a time when some of their employers are on campus. That way, “our voice is not the only voice that’s being heard,” he said.

Another strong point for UTI is its original equipment manufacturer or OEM relationships.

“I do believe that the power of a manufacturing community, the power of the employment community and the power of our student voices together create something that’s much larger,” Grant said. In addition, he said working more closely together provides a way to move forward.

For example, when California was proposing legislation that would have made UTI limit the number of military students on their Long Beach, Rancho Cucamonga and Sacramento campuses, Roger Penske of Penske Trucking talked to legislators since Penske hires 700 or 800 of their graduates every year. “Penske said, ‘Do you understand how many job openings I have right now?’” Grant said. “[He told them] narrowing the tributary of skilled workers right now is the exact wrong thing to do.”

Employers have a lot more clout with Congress then an individual person does, Cohen agreed, noting they need to continue to nurture those relationship with employers.

“We have articulation agreements with about 1,5000 employers, some very deep, some very shallow,” he said. “Candidly, some have said, ‘Look, we appreciate what you do, but that’s a political battle we’re not getting into.’ And so some of them don’t want to be publicly standing up for the industry, even though they need the industry in order to provide education and outcomes to their employees.”

Altmire said it is no coincidence that this discussion was taking place just as there was a major announcement about ITT and borrower defense at the Department of Education. In June, the DOE announced the approval of 18,000 borrower defense to repayment (borrower defense) claims for individuals who attended ITT Technical Institute. These borrowers will receive 100% loan discharges, resulting in approximately $500 million in relief.

So how do career education schools overcome publicity like that?

Grant said schools need to focus on being aggressive in publishing outcomes and giving people the data they need to make rational decisions, rather than fighting a fight of the past.

Cohen agreed. “We’ve published an academic annual report for the last 12 years in a row,” he said. “It has all of our outcomes in it. We give that to every congressional leader and policymaker whenever we meet with them in order to make sure they do understand what we are focused on.”

In addition, the University of Phoenix just recently introduced their Career Optimism Index and the Career Institute to focus specifically on research opportunities and careers and how education and careers are connected.

“We’re trying to make sure that the general public knows that we are research-driven,” he said. “We have industry advisory councils that create all of our programs and assure that our programs are aligned to the needs of industry.”

Cohen said they also agree with the concept of accountability.

“We want our students to have good outcomes and we want to hold ourselves and everybody else, whether it’s a tax-exempt or taxable institution, accountable for the investment students are making in their education and the money they’re spending,” he said. “We take government funds, and if you take government funds, you should (be) accountable. Everybody should be in every industry.”

PETER COHEN, with more than 20 years of leadership in the education and learning science sectors, was appointed the eighth president of University of Phoenix in April 2017. The University of Phoenix serves about 98% of their students online today in fields such as business, information technology, health care, social services and education, although they started as a campus-based business back in 1976. Prior to joining the University of Phoenix, Cohen served as executive vice president of McGraw-Hill Education. He was also group president of U.S. Education at McGraw-Hill, overseeing the company’s U.S. K-12 and higher education businesses. Previously, Cohen served as CEO of Pearson Education’s school division, where he was instrumental in shifting the company’s focus toward digital resources and expanding its school services.

JEROME A. GRANT was named executive vice president and chief operating officer at Universal Technical Institute in November 2017, and was named CEO and nominated to UTI’s Board of Directors in 2019. He served as senior vice president-chief services officer for McGraw-Hill Corp. from June 2015 to April 2017. Prior to that, he served for more than 14 years at Pearson Education, Inc., where he had multiple executive roles and led their digital product management group through the initial stages of their digital transformation. He has more than two decades of executive leadership experience in postsecondary education, including digital strategy, strategic partnerships, marketing and technology.