NACIQI, ED.Gov, CHEA Offer Guidance Regarding COVID-19-Era Quality Assurance

By Anthony S. Bieda, www.asb34policyresources.com

The global pandemic disrupting instruction in higher education is also re-shaping some of the highly routinized, methodical quality assurance protocols of accreditation. Recognition authorities who are responsible for assuring reliable, credible accreditation are evaluating the adjustments and accommodations made to quality review and institutional accountability in an era of virtual, rather than physical face-to-face peer encounters.

To date, the evaluations may be considered inconclusive regarding 1) the effectiveness of proxies for in-person review, 2) the rigor of virtual accreditation protocols, and 3) the impact of deferred face-to-face encounters on student satisfaction, student achievement, facilities quality and the sufficiency of on-ground equipment and materials.

A clearer focus is emerging, however, regarding the areas of concern and interest for the quality assurance discipline, in general, and the accreditation enterprise in particular.

The analysis that follows considers available written disclosures from the accreditation community and the primary sources of guidance regarding accreditation recognition: The U.S. Department of Education’s (ED.Gov) Office of Postsecondary Education, the National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity (NACIQI), and the Council on Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA).

Authorities over online instruction, accreditation

To serve as reliable authorities on institutional quality and integrity, accrediting bodies in the U.S. must achieve initial recognition from ED.Gov (and/or CHEA) and submit to periodic renewals of their authority through a rigorous process prescribed by federal statute and administrative code.1 Those processes, continuously active through the first and second quarters of 2020, provide important perspective through case studies, accreditation guidance bulletins, recognition reports and meeting transcripts on the state of accreditation in the COVID-19 era.

Quality assurance is applied through the entire higher education oversight triad, which includes accreditors, state authorizers and professional licensure boards, as well as the federal government. All three sides set expectations and enforce standards regarding education quality in different ways. All three routinely communicate their expectations to the other triad partners and education providers. Conflicts in standards may be reconciled through the application of permissive language, deferential courtesy, deferred time intervals or explicit, default adherence to the most stringent standard, regardless of source.

Behaviors which resolve conflicts in standards are germane to the evolving protocols of quality assurance in the COVID-19 era. Risk from in-person contact derived from the pandemic has not only curtailed face-to-face instruction, it also has constrained in-person peer reviews that are considered integral to effective, credible accreditation. In lieu of direct observation and in-person encounters, oversight partners have scrambled to create virtual protocols that substantially accomplish satisfactory reviews through online technology, telephonic conferences, email correspondence and other low-contact activities. While proxies for in-person instruction have attained a certain level of acceptance, virtual accreditation reviews of postsecondary education are novel, untested and in want of a deep body of case studies, quantitative research or published ethnographic inquiry.

Absent a deep well of best practices or evidence-based protocols from which to draw model, virtual accreditation activities, triad partners have been encouraged to design and implement online and at-a-distance quality audits while honoring an implied list of assumptions:

- At minimum, virtual reviews as proxies for mandatory in-person site visits will continue through December 31, 2020, if not later.

- Acceptance of virtual reviews as proxies for in-person review by recognition authorities and other triad partners is conditional, temporary, and valid only as an accommodation of the pandemic.

- During the pandemic, substituting a required site visit with a virtual encounter must occur in the same or nearly the same timeframe as the originally scheduled site visit.

- Unless otherwise authorized in writing, the virtual review must be followed in a timely manner with a subsequent site visit to further verify information considered during the virtual review.

- Creativity and innovation in accreditation during the COVID-19 era are tolerated but must be documented, rationalized, and explained to recognition authorities. Contemporaneous notification of creative or innovative accreditation activities is expected as well.

Furthermore, evaluating the state of accreditation in the COVID-19 era merits awareness of other core principles that tie together quality assurance across state and federal jurisdictions, entities, and sectors. Those principles include a grounding in the best interests of students and their achievement through learning; that education practices observed and reviewed through any modality must be documented with narrative and evidence; and that deviation from standard accreditation practices, regardless of the impetus, creates a burden of proof on the accrediting entity. Finally, the suspension of in-person, physical evaluation does not suspend or defer in any way the obligation of an accredited college or school to demonstrate accountability and effectiveness as measured by standards developed and applied before and during the pandemic.

Considerations enumerated above are by no means exhaustive or comprehensive; rather they reflect the more salient issues manifest in contemporary evaluations of the quality assurance enterprise during COVID-19. More plainly, recognition authorities and their influencers are paying close attention to how accreditors adapt to the constraints of low-contact/no contact review, the degree to which their accommodations diminish or undermine tests of rigor, and which standards are waived or deferred and for what reasons.

NACIQI and COVID-19 quality assurance

A primary source of recognition policy, the U.S. Department of Education’s National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity (NACIQI) owns the capacity to make timely, authoritative review of accreditation performance. Information resources at the Committee’s disposal include detailed reports from professional accreditation experts in the Department’s Accreditation Group, responses from accredited colleges and schools, direct testimony in front of the Committee, public commentary and other Department-generated studies and white papers.

By statute, the Committee’s primary purpose is to advise the Department on accreditation policy that helps to ensure effective expenditure of federal student aid grants and loans. In the case of the Department’s authority over Title IV financial student aid, quality assurance is transformed from an abstract exercise into tangible gatekeeping with stakes measured in the billions of dollars.

Before accreditation can become material to Title IV participation decisions, NACIQI toils in the abstract domain of recognition criteria. The committee applies the Department’s recognition standards at least twice a year to accrediting bodies through public, periodic renewals of recognition. Absent ED.Gov recognition, an accreditor’s colleges and schools are unable to offer federal student aid.

In July 2020, five months into the pandemic outbreak, the Committee formally reviewed the accreditation performance of several accrediting bodies using its standard recognition process.

The review intervals involved were such that most of the evidence regarding quality assurance of the COVID-19 era postsecondary education was limited to that collected from virtual reviews conducted in April or May. Typically, the performance evidence of a recognition dossier comprises at least a few years of accreditation activities involving dozens of colleges and schools.

With those limitations noted, the Committee considered available evidence from Department staff and accreditation agencies to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on the assurance of education quality and institutional integrity. Among NACIQI’s areas of focus:

- Lack of in-person accreditation review of physical aspects of the school, including lab space, materials, equipment.

- Virtual practical instruction as a proxy for clinical experiences/externships.

- Rigor of desk-based reviews compared to in-person reviews of records, observations of instructional activities, inspection of facilities and interviews with faculty, students, staff.

- Timing of desk reviews relative to interval established by accreditation criteria.

- Timeframe for follow-up in-person reviews to supplement virtual reviews and verify evidence and records.

- Potential non-compliance with the requirement of site reviews by all accreditors, even in the COVID-19 era.

The Committee paid close attention to items A, B and C as applied to an allied healthcare accreditor. In one case, the accreditor used Zoom teleconferencing to conduct a virtual site visit, then reviewed a video of the facilities, materials, and equipment to evaluate standards regarding physical capacity.

NACIQI heard representations from the accrediting community and ED staff that clarified important aspects of the virtual site visits: 1) The virtual visit must review all of the standards that would be reviewed during an in-person review; 2) They must be followed in a reasonable time-frame with an on-site review to further verify the evidence provided virtually; 3) The follow-up site visit can be more focused, using a smaller evaluator team than was deployed during the virtual review. Also, of note, NACIQI expects fidelity to the interval between accreditation reviews as required by the accreditor’s own policies, even during the COVID-19 era. In other words, COVID-19 on its face is not a sufficient reason to defer a scheduled review into the indefinite future.

The sufficiency of simulated or virtual practical instruction as a proxy for in-person, hands-on learning is of interest to the Committee. Colleges and schools that offer programs designed to prepare graduates for employment in professional, technical, or occupational fields (such as patient care, cosmetology, veterinary care) typically require practical instruction of duration and intimacy sufficient to meet state licensure requirements. To the degree state licensure boards have prescribed acceptable virtual proxies for hands-on practical experience, the accrediting bodies in some cases have deferred to the state board. That is, the accreditor assumes that the quality assurance requirement is fulfilled if the clinical proxy meets the requirements of the state licensing authority.

Specificity and clarity about virtual versus in-person practical remains elusive. Perhaps indicating pent-up demand for timely best practices and evidence-based prototypes, one accreditor reported reviewing “more than 400 proposals” for alternative types of clinical experiences since COVID-19 began. Regardless of the subsequent innovations in virtual externships, the Committee reiterated that an accrediting agency must be prepared to defend its forays into innovation; the burden of proof (demonstrating sufficiency of the method) will fall on the accreditor.

While the Committee’s deliberations on these topics were not necessarily conclusive, it is clear how subsequent petitions for recognition derived from COVID-19-era accreditation will likely receive elevated scrutiny and analysis by this independent advisory body. The Committee expressed a certain degree of flexibility and tolerance for innovation in quality assurance; yet it reiterated that core principles and assumptions that have not been waived or marginalized due to the pandemic.2 In one instance, NACIQI expressed chagrin that an accreditor who performed numerous “desk reviews” (virtual evaluations) in lieu of in-person site visits failed to offer the Department either a sample of a “desk review” template or procedure, or cared to discuss what constitutes a sufficient “desk review” under its own published standards. Clearly, specifics, examples and written evidence will continue to be expected elements of any diversion from accepted accreditation practices, COVID-19 notwithstanding.

ED.Gov and COVID-19 accreditation

Statutory authority for recognized accreditation is the domain of the Department. Through policy, legal and planning divisions, the Office of Postsecondary Education determines what types of accreditation are sufficient to qualify an institution to participate in federal student aid programs. While the NACIQI exercises important review and policy development functions, ED.Gov’s professional staff are ultimately responsible for assuring quality among Title IV-receiving colleges and schools.

To that end, ED.Gov has offered some preliminary guidance on preserving effective quality assurance review even when traditional in-person, on-the-ground peer encounters are unavailable.3

While the consequences of marginalizing or ignoring preferences of the Committee may not be catastrophic, defying explicit and implied expectations of ED.Gov professional staff has arguably greater consequences. Ultimately decisions to recognize or deny recognition rest with the senior Department official, not the advisory body.

With that caveat in mind, accreditors are attentive to recent Departmental pronouncements that augment the quality assurance expectations of NACIQI in the COVID-19 era. Some highlights:

- Virtual site reviews as proxies for in-person evaluation are permitted but not mandatory. They should include the same cadre of trained evaluators, using the same criteria and making the same document reviews that would be deployed during an on-site visit.

- Virtual site reviews should not solely rely on the exchange of emails, documents, or text messages; they should reflect an engaged, interactive interchange, such as telephonic conferences, video calls or other technology platforms.

- Follow-up visits to verify virtual reviews may be focused, but at a minimum must include interviews with students selected at random, observation of online or other distance education modalities in real time, and inspection of facilities, equipment, and materials.

- Flexibility in the verification of high school completion or its equivalency is permitted.

- Waivers of certain requirements for ‘Return to Title IV’ funds that are attributed to student withdrawals due to COVID-19 are allowed.

- Flexibility in excluding credits attempted but not completed due to COVID-19 is permitted.

- Exclusion of up to 12 credits taken in the COVID-19 era toward the calculation of maximum timeframe (Satisfactory Academic Progress) is allowed.

- Some allowance is acceptable for classes to be graded on pass/fail basis in fulfillment of SAP requirements.

- Term of accreditation may be extended for a reasonable period during the pandemic; this permissive consideration applies to accreditation renewals, resolution of show-case orders or probations.

Rather than considering these topics exhaustive in scope or final and permanent, they may be deemed thematic and illustrative. Department staff is encountering new data and information continuously as it reviews and analyzes recognition petitions from the 3rd and 4th quarters of 2020, and receives commentary from institutions, students, and the broader community. The newer intelligence will likely further shape the next iterations of policy.

Notwithstanding the dynamic, interim nature of the COVID-19-era recognition policy, the Department’s durable guidance merits a closer look. Of note is a recurring theme of accountability, as well as demonstrated fidelity to rigor and process in the development, vetting and implementation of innovative methods of quality assurance. The Department’s accreditation group is explicit about expecting an accreditor to produce, upon request, documents that show how, when and who was involved in creating quality review policies unique to the CV 19 circumstance. Further, in accord with recognition criteria, the policy must have been shared with stakeholders and the public, and the accreditor should be able to document how the resulting feedback helped shape the final policy. Finally, while the Department waived the requirement that the policy be ratified by a majority of the decision-making body at an in-person meeting, it remains steadfast in requiring the governing board to review and adopt the temporary refinements to policy through a recorded vote “in writing.” The policy revisions must be posted to the accreditor’s website.

The Department cautions that accreditation grants may be extended beyond the maximum timeframes allowed under regulation, but that extensions must be made for “good cause,” demonstrated and documented for review.

In summary, the Department offers flexibility to recognized accreditors as a partial accommodation to the pandemic but applies conditions and sideboards that are worthy of review and exploration. Its guidance and pronouncements reinforce the theme of temporary and finite: once the pandemic has abated and in-person modalities resume, normal accreditation and quality assurance protocols are expected to resume as soon as possible. In the interim, deviations from in-person-based accreditation protocols must stay within the Department’s parameters, the deviations must be documented and recorded, and the burden of proving effectiveness lies with the recognized accreditor.

CHEA and COVID-19 accreditation

The Council on Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) is a self-governing recognition entity for accreditors of programs at the associate degree and higher. It does not offer recognition to accreditors whose colleges and schools offer primarily certificate, diploma, and other non-academic credentials.

Unlike the Department’s recognition division whose primary purpose is stewardship of federal student aid, CHEA’s recognition standards emphasize student learning, student achievement and institutional performance and accountability.

When the primary and preferred mode of delivering instruction in the service of student learning is compromised by a pandemic, CHEA’s oversight takes notice: “Student dissatisfaction” with mandatory online instruction has raised concerns at CHEA. More elaborately, CHEA has acknowledged that the link between the student’s financial (let alone spiritual, emotional and temporal) investment in a credential and the in-person instructional modality has become stronger and more explicit: in a word, CHEA recognizes that many students feel “cheated” sitting in front of a computer to obtain college-level instruction.

If disruption to the preferred instructional modality were temporary and necessary only for the duration of a short-lived public health emergency, concerns of recognition may have manifest only superficially. Because the disruption has persisted through the Spring, Summer and Fall 2020 academic cycles, CHEA has given additional scrutiny to remedies proposed and implemented at most colleges and universities accredited by agencies bearing its imprimatur.

CHEA observes that while all accreditors of colleges and universities typically applied standards to on-ground instruction, many of the institutions that adopted online modalities in response to the pandemic had been subject to specific standards for distance education beforehand. The upshot of the discussion: accreditation standards for online education must be applied to colleges and universities that have adopted online modalities in the COVID-19 era. Or in other words, the erosion of student learning due to a change in instructional modality is not to be tolerated.

Unique in its focus on student learning and the attendant outcomes, CHEA has emphasized three core aspects of the student experience:

- Academic quality and rigor derived from instructional activities.

- Access to and strength of extra-curricular activities.

- Opportunities for social interaction between students.

A common thread tying these together is student engagement. Absent specific tactics and strategies in the online classroom, student engagement in the academic process will diminish. Absent deliberate, alternative opportunities for extracurricular activities and social interaction, student engagement with non-academic institutional resources will atrophy, yielding lower academic achievement and learning.

Regarding student engagement in the academic setting, CHEA encourages re-engineering course content, scope and sequence of programs, class scheduling, the pacing of assignments, and rubrics used to grade assignments, among other factors. Furthermore, CHEA recommends close attention to the preservation of access to and interaction with faculty and classmates notwithstanding limitations derived from distance education modalities.

CHEA dives deeper into the core of the instructional discipline by considering the appropriateness of synchronous vs. asynchronous content delivery; the degree of immersion in course content; adoption of competency-based instruction; and the rigor of clinical and laboratory encounters transitioned to virtual experiences/simulations. The Council encourages accreditors to review how institutions initiate and demonstrate that faculty have been trained to deliver interaction and enrichment using online modalities. It encourages the review of evidence of student learning in faculty evaluations and advises the application of student learning evidence to the assessment of institutional effectiveness. CHEA also advises accreditors to ensure that students who are displaced by the pandemic are held harmless when their recovery involves the transfer of academic credits to another college or university.

In summary, CHEA expresses expectations that student learning and achievement, as well as institutional evaluations of effectiveness, remain high priorities even during a prolonged displacement from in-person education. The Council establishes a point of reference, through its published guidance, that the temporary and immediate cessation of in-person, face-to-face modalities does not constitute a waiver from expectations of quality, effectiveness, and accountability.

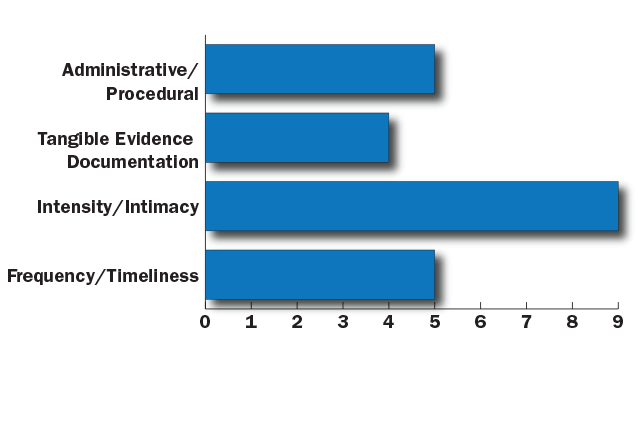

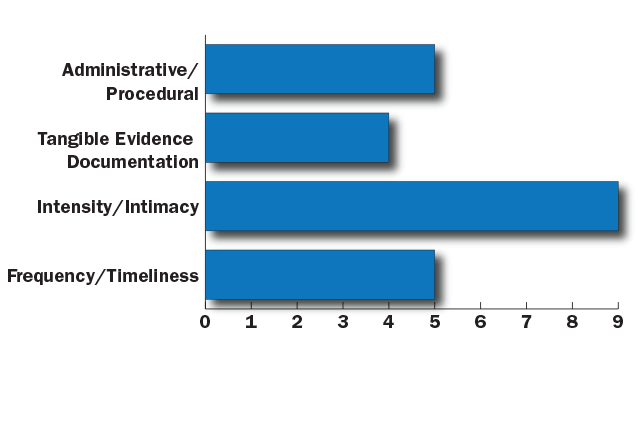

Quality Assurance Issues Derived from COVID-19-Era Review of Postsecondary Education

Concluding considerations

Effective quality review of postsecondary education requires systematic application of written standards, replicable procedures and sufficient experiential, informational and financial resources. Its primary means of inquiry include the review of documents and records, direct observations of instructional activities, and candid interviews with students regarding their satisfaction and fulfillment. Restrictions on group-based, in-person activities imposed by a pandemic impede the use of incumbent methods and accreditation protocols. The same restrictions limit the instructional modalities available to the accredited colleges and schools who directly, if not literally, touch the learning outcomes of students each day.

The entire hierarchy of oversight applied to education quality at the postsecondary level is responsible for ensuring the value received by students.

A reasonable assumption is that the responsibility is not diminished or waived during a pandemic outbreak: students are still pursuing knowledge, and the providers of knowledge have obligations as part of the value transaction.

Short-term, judgement has been suspended regarding the comparability of online education to on-ground; the rigor of physical team visits versus virtual evaluations; and the suitability of simulated clinical and laboratory experiences compared to in-person encounters with patients, clients, materials and equipment. Driven perhaps by a persistent groundswell of resistance to online, virtual, and simulated education from students, parents, employers, and the community, the oversight hierarchy is attentive to the risks to quality posed by alternative modalities.

Thoughtful, tangible, and defensible mitigation of those risks is left primarily in the hands of the institutions who deliver instruction or who assure quality through recognized accreditation. Yet authorities over education funding and accreditation recognition have reiterated their stake in quality notwithstanding a global pandemic. And they have begun to articulate interim as well as sustained expectations in service to student interests. Tolerance for lapses in quality attributed to the emergency and temporary nature of the COVID-19 outbreak is shrinking and may soon evaporate.

References

- Provisions of the Higher Education Act of Congress, which authorizes the administration of federal student aid to accredited colleges and schools.

- Source: Transcripts from NACIQI Meeting, July 2020 via Webex

- Ed.Gov offers recognized accreditors the option to execute site reviews in-person or using virtual proxies, however, the accrediting community follows the guidance of the relevant state public health authorities, typically expressed as a gubernatorial decree, in deciding whether or not to send an evaluation team to a campus.

ANTHONY S. BIEDA, for more than 40 years, has served a leader and member of executive teams with primary responsibility for government relations, policy advocacy and organizational communications.

He has served in public and private higher education, local government operations and services, natural resources, telecommunications, and economic development.

Bieda has completed doctoral-level coursework in public policy at George Mason University in Virginia. He earned an MBA in accounting and finance from Regis College, and undergraduate degree at University of Northern Colorado in Journalism.

He recently served as executive director of the Kentucky Association of Career Colleges and Schools. He continues to serve clients in government relations, accreditation, strategic communications, and advocacy planning capacities. He is based in Louisville, KY.

Contact Information: Anthony S. Bieda // ASB34Policy Resources, LLC // 703-399-9172 // anthonysb34@msn.com // http://asb34policyresources.com/