Quality, Accountability and Action – Part 1

By Linda Baer, Ph.D.; Copyright 2015; reprinted by permission of ACICS

The times are changing for higher education in dramatic ways, at warp speed. What will institutions need to do to move boldly in this changing environment? It could be argued that leaders will need to create the capacity and environment to move while preserving the values and core missions that make their institutions strong. Leadership will confront determinations about what made institutions strong in the past versus what will make them strong in the future. Strength in terms of articulating the value their institutions provide students, communities, and society as well as strength in terms of sustainability in a dynamic environment. Leadership must identify future trends and needs, lead change agendas, invest in what makes a difference, and remain authentic and courageous.1

To begin, what has changed?

The Society for College and University Planning regularly posts Trends to Watch in Higher Education, an environmental scan of the forces at play related to demographics, economics, environment, global changes, technology, learning and politics.

Today’s changes are more powerful than ever, including intense competition among traditional institutions, expansion of for-profit institutions, technological advances, globalization of colleges and universities, and demands for accountability and return on investment.

Among several key changes, four in particular – Demographics, Expectations, Economics, and Technology – deserve substantial attention from leaders and facilitators of change:2

People of all backgrounds continue to seek educational opportunities to improve their lives, making the population of students attending college more diverse than ever. “The profile of today’s college-going population looks much different than it did decades ago, when the average student was a fresh-faced 18-year-old moving directly from high school to campus. Students today are older, more experienced in work, and more socioeconomically and racially diverse than their peers of decades past.”3

Over 50 years, educational opportunity has increased in American higher education. Thirty-one percent of those 25 and older hold a bachelor’s degree – two and a half times the rate in 1970.4 Yet there have been stagnant or falling completion rates over the past decades.5

The profile of students is changing. Currently, American higher education enrolls 17.6 million undergraduates. The National Center for Education Statistics reports that just 15 percent attend four-year colleges and live on campus. Forty-three percent attend two-year institutions; 37 percent of undergraduates are enrolled part-time and 32 percent work full-time. Of those students enrolled in four-year institutions, just 36 percent actually graduate in four years.

The most significant shift is probably the massive growth in the adult student population in post-secondary education.

Thirty-eight percent of those enrolled are over the age of 25 and one-fourth are over the age of 30. The share of all students who are over age 25 is projected to increase another 23 percent by 2019. 6

Far more people seek educational opportunities, and in general they are less prepared than earlier generations. Students are far more diverse including adult learners, veterans, and students of diverse ethnic backgrounds. While enrollments have grown during the past decades, the persistence and completion rates have changed little during the past 30 years. Dismal completion record is not acceptable; stakeholders demand greater student success.

Expectations

At one time in higher education, the outcome of the student was assumed to be nearly exclusively derived from his or her talent, effort and persistence. Today, students are no longer expected to succeed or fail based only on their own merits. Institutions must invest in student and academic support systems to improve student success. Expectations of accountability, transparency, and integrity of outcomes are now the norm. The change is away from an emphasis on open access to colleges and universities and toward unconditional expectations of student success. The expectation includes institutional demonstration of a strong understanding and application of appropriate metrics, leading to actions that empower student success.

However, no strong consensus exists between social scientists, institutional effectiveness experts and public policy entrepreneurs regarding appropriate ways to measure and evaluate post-secondary education.

Many in the higher education rankings business favor metrics that do not focus on teaching and learning.

In a CHEA presentation in early 2015 based on a publication on World University Rankings 2014-2015 methodology, an international publisher presented the following five areas as performance indicators:

- Teaching: the learning environment (worth 30 percent of the overall ranking score)

- Research: volume, income and reputation (worth 30 percent)

- Citations: research influence (worth 30 percent)

- Industry income: innovation (worth 2.5 percent)

- International outlook: staff, students and research (worth 7.5 percent)7

Not a single factor applied to learning outcomes, such as retention and persistence; completion, graduation, placement, pass rates for licensure exams, cumulative GPA, graduate satisfaction rates, employer satisfaction rates, comprehensive portfolio review, or satisfactory completion of externships. (Times Higher Education 2015.)

Economics

The fundamentals around how students pay for education amid rising costs have changed. This has resulted in a shift from grants to loans and from state support for a majority of the cost to student tuition. The current economic times coupled with current higher education business models do not support student access, affordability, or success in a sustainable manner. Moreover, current models are incapable of supporting or sustaining institutions in the long term.

Technology

The need to support academic technology continues to rise. The Horizon Report for Higher Education 20148 lists six key trends to attend to as part of developing future-sustainable strategies:

- Growing ubiquity of social media

- Integration of online, hybrid, and collaborative learning

- Rise of data-driven learning and assessment

- Shift from students as consumers to students as creators

- Agile approaches to change

- Evolution of online learning

While technological communities resonate with these trends, within our institutions, academic technology is expected to play a major role in support of access, affordability, student success and institutional sustainability. Robust data warehouses empowered by data mining and analytical tools are critical within this rapidly changing environment. If performance metrics are to be identified, targeted, measured and most importantly, analyzed to improve the higher education learning environment, then major attention must be devoted to institutional data, research and analysis.

Norris et al. emphasize in Transforming in an Age of Disruptive Change: “We are starting to face multiple combinations of challenges. In previous decades, these challenges occurred singly and independently. If the multiple-challenge trend continues, then higher education could face a new ‘perfect storm’; declining authority, unfavorable economics, new competition, and reduced career opportunities for new graduates.”9 (Norris, 2013.)

Indeed, the “perfect storm” has come. Most institutions believed that these circumstances would pass and that they could return to “normal.” Yet there is no normal or going back.

The “new normal” compels institutional leaders to change the way they approach students, learning and sustaining our institutions. It requires that leaders become agents for change and transformation.

To do so, most institutions have undergone some form of strategic planning or strategic positioning; however, the majority of these efforts have not resulted in transformative change (See Dolence & Norris, 199710 , Kanter, 200111 , Rowley, Lujan, & Dolence 199812 , Norris et al., 2013.13 ). Institutions continue to reorganize, restructure, reallocate, and retrench activities in response to ongoing shortfalls and changing learning demands. Such changes are incremental in nature and occur at the margins of the organization. Once again, they do not support or sustain student access, affordability, or success in large enough numbers, and they do not result in supporting and sustaining our institutions.

Accountability

Accountability is defined as “an obligation or willingness to accept responsibility or to account for one’s actions.”14

Accountability imposes six demands on officials or their agents for government or public service organizations including colleges and universities.

- Demonstrate that they have used their power and authority properly.

- Show that they are working to achieve the mission or priorities set for their office or organization (such as meeting or exceeding accreditation standards).

- Report to the public and the various stakeholders of their performance, for “power is opaque, accountability is public.” (The accreditation community, state approval entities and the major funding source of post-secondary education, the U.S. Department of Education, have written standards and requirements regarding transparency and accountability.)

- Efficiency and effectiveness require accounting for the resources used and the outcomes they create.

- Ensure the quality of programs and services produced (the accreditation community has strong, explicit standards).

- Serve the public need, as defined in the broader sense and in the more narrow sense as defined by the Council on Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) and the Higher Education Act15 (HEA; Burke 2).

For institutions to survive or even thrive in the era of “the new normal,” they must move boldly, guided by leaders who understand accountability, metrics and analytics. While many authoritative voices aspire to define quality through accountability and performance, it is most closely linked with the assessment of quality by private, independent and self-governed entities known as accrediting councils. However, deference to accreditation review of quality is becoming conditional and contingent; the momentum of demand for greater accountability is encountering the inertia of tried and true but sometimes opaque methods of accreditation.

“New normal” factors driving the demand for accountability include a strong focus on student success, reduced funding, rising costs and the push for more cost-effective solutions.

Institutions are pressured to demonstrate return on investment made by learners for education and the subsequent outcomes gained in employment and careers. In addition, new models and structures of delivery have moved the dial on how we assess learning and student success.16

The array of higher education stakeholders demanding more accountability, as well as greater evidence of innovation and quality in higher education, is broad and substantial. Recent examples include the White House College Scorecard; U.S. Department of Education’s proposed College Rating System; the proliferation of online college consumer information clearinghouses; and “Education Should Strengthen Oversight of Schools and Accreditors.17 Some hold a stake as providers of funding; others as protectors of consumers; and still others as policy makers or policy shapers, deliberately or unintentionally developing requirements that will advantage some organizations to the detriment of others in the same sector or industry.

In the case of funding sources, consider that among the Top 10 Higher Education State Policy Issues for 2015, the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU) cited performance based funding as a high priority. States have been shifting from enrollment to Performance-Based Funding (PBF) for public colleges and universities during the last several years. The National Council of State Legislators (NCSL) reports that more than half of the 50 states now have PBF in place, with wide variations in performance metrics applied and the amount of state funding distributed based on performance. After having PBF systems in place for several years, it may now be possible to see if they have served as catalysts for improving campus outcomes.18 (Hurley, 2015.) But if campus-level outcomes are a function of performance at sub-campus levels, do PBF systems have the capacity to evaluate and award effectiveness at the program level, or even the individual course level? In terms of organizational hierarchy, it could be argued that quality and effectiveness at the individual course level beget effective programs, and effective programs are pre-cursors to quality institutions. Should performance-based funding models then favor effective courses and programs over ineffective ones?

Quest for quality

But what is quality in general, and in post-secondary education in particular? Is it primarily a function of inputs and outputs, keeping rules and reaching standards, fulfilling stakeholders’ needs and expectations? Is quality about the education institution assuming accountability and through metrics, creating opportunities for people to become self-empowered through knowledge? In fact, to what extent does quality link to performance, competitiveness or excellence? What is the evidence showing that quality generates performance and that performance cannot be reached without applying quality concepts, principles, models, and eventually systems?19

The five dimensions of quality as determined by Sandru are:

- Quality as exceptional (e.g., high standards);

- Quality as consistency (e.g., zero defects);

- Quality as fitness for purpose (fitting customer specifications);

- Quality as value for money, (efficiency and effectiveness); and

vQuality as transformative (an ongoing process that includes empowerment and enhancement of customer satisfaction).”20

Sandru concludes that the challenge is to decode the mechanism that makes these dimensions interact and stick together. In higher education, the evidence and measures of quality are closely tied to accountability and performance.

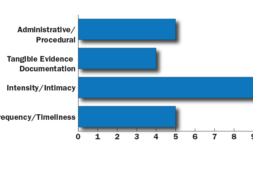

Decoding the connections may be the key to moving accountability from reporting to action and establishing an even more critical role in the formation and application of accreditation standards. The following is a chart that takes the Sandru performance measures and determines benchmarking activities with which to compare outcomes.

| Metrics of Quality | |

| Exceptional Performance | Benchmarked against peers, aspirations, historical data, national data, other |

| Consistency and Transparency | Activities result in similar results over time and over populations served; activities and outcomes reported openly |

| Value | Return on investment, outcomes expected for price, placement, gainful employment |

| Fitness for Purpose | Delivering on mission for stakeholders |

| Transformative | Flexibility, resilience, innovation, culture of change, business models that support transformative activities. |

A resource produced by Linda Suskie21 (2015) is an outstanding practical guide to assessment, accountability and accreditation. Suskie describes five dimensions of culture: relevance, community, focus and aspiration, evidence and betterment. Relevance reflects doing the right thing in meeting responsibilities, putting students first, knowing stakeholders needs, keeping promises and serving the public good. The culture of community begins with respect, communication, documentation and collaboration. Its foundation is supporting growth and development of expertise across the institution. It includes a respect for shared governance.

The culture of focus and aspiration claims the purpose of the institution that knows where it is going and how it wants to get there. It is based on systematic evidence and collaboration with a clear understanding of targeted clientele. The culture of evidence is about how the institution gauges success: i.e., student success and student learning, economic development, responsiveness to the changing student population, contributions to the common good, and achieving college purpose and goals. Finally, the culture of betterment is based on using evidence to ensure and advance quality and effectiveness.

The key to understanding these five dimensions is the interrelations between them:

“A quality college not only ensures and advances all five cultures of quality but appropriately interrelates them. Regional accreditors are unanimous, for example, in believing that a quality college links goals, plans, evidence, and resource deployment decisions. Goals inform assessment strategies and resource allocations, while evidence informs goals, plans, and resource allocations. In other words, the culture of focus and aspiration (goals) affects the culture of evidence (assessment) and the culture of betterment (resource allocation). The culture of evidence, meanwhile, informs the culture of focus and aspiration (goals and plans) and the culture of betterment (resource allocation).”22

Who defines quality? Why is it important?

For more than 100 years, accreditation has been the primary vehicle for defining and assuring quality in post-secondary and higher education in the U.S.

“In this complex public-private system, recognized accreditation organizations develop quality standards and manage the process for determining whether institutions and programs meet these standards and can be formally accredited.”23 Accrediting organizations play a key “gatekeeper” role because accreditation is used to determine whether higher education institutions and programs are eligible to receive the more than $130 billion in federal and state grants and loans available in the current federal fiscal year, which serves to inform and protect consumers against fraud and abuse.

Shray continues with a focus on three major sets of questions and issues related to accreditation:

- Assuring performance. How can the accreditation system be held more accountable for assuring performance, including student-learner outcomes, in accredited institutions and programs?

- Open standards and processes. How can accreditation standards and processes be changed to be more open to and supportive of innovation and diversity in higher education including new types of educational institutions and new approaches for providing educational services such as distance learning?

- Consistency and transparency. How can accreditation standards and processes be made more consistent to support greater transparency and greater opportunities for credit transfer between accredited institutions?24

Shray concludes that “while the accreditation system has taken steps in recent years to address these issues, after almost 20 years of dialogue and debate, there is still no clear consensus on how to change accreditation to respond to these new demands.” 25

The formation and application of quality assurance standards must be considered in the context of the two types of accreditation organizations – institutional and specialized or programmatic. Shray expands on the formal definitions.26

- Institutional Accreditation. National and regional institutional accreditors review entire institutions and assure the quality of more than 95 percent of all students enrolled in post-secondary education in the U.S. National accreditors review colleges and schools throughout the country, while regional accreditors focus their efforts in prescribed geographic territories. National institutional accrediting agencies have quality assurance authority over more than 3,400 institutions: 35.9 percent are degree-granting; 64 percent are non-degree granting; 20.9 percent are non-profit and 79 percent are for-profit. Many are single-purpose institutions (e.g., information technology.) Of the 2,963 regionally accredited institutions, 97.4 percent are traditional, non-profit degree-granting colleges and universities. All institutional accreditors recognized by the U.S. Department of Education serve as gatekeepers to Title IV – Federal Student Aid (FSA) participation.

- Specialized Accreditation. Specialized accrediting agencies operate throughout the country and review programs, departments, or schools in specific fields (e.g., business, law) that are parts of an institution. Some specialized accrediting organizations also accredit professional schools or other specialized or single purpose institutions. Some specialized accrediting agencies are state government agencies such as agencies responsible for regulating healthcare professions. There are 18,713 of these accredited programs and single purpose institutions. Many do not play the role of providing institutional access to FSA participation.27

*References will be provided in Part 2 of this article.

Dr. Linda Baer has served for more than 30 years in executive positions in higher education including Senior Program Officer in Postsecondary Success for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Senior Vice Chancellor for Academic and Student Affairs in the Minnesota State College and University System, Senior Vice President and Interim President at Bemidji State University. She recently served as the Interim Vice President for Academic Affairs at Minnesota State University, Mankato. Her ongoing focus is to inspire leaders to improve student success and transform institutions for the future. Recent publications have been on smart change, shared leadership, innovations in higher education, transforming in an age of disruptive change, and analytics as a tool to improve student success.

Citations

1Baer, Linda and Ann Hill Duin, Deborah Bushway. Change Agent Leadership. Planning for Higher Education.V.xxNx. April-June, 2015.

2 Ibid pp

3Merisotis, 2015

4Frey and Parker, 2012

5Bound, et al, 2007

6Hess, 2011

7World University Rankings 2014-2015

8On the Horizon 2014.

9Norris et al 2013

10Dolence & Norris, 1997

11Kanter, 2001

12Rowley, Lujan, & Dolence 1998

13Norris et al 2013

14Merriam-Webster 2003

15Burke, 2

16Schray, Vickie. Assuring Quality in Higher Education: Recommendations for Improving Accreditation. https://www2.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/hiedfuture/reports/schray2.pdf

172013 State of the Union Address; www.ED.Gov; GoRanku.com; GAO, January 2015

18Hurley, 2015

19Sandru, Ioana Maria Diana. 2008. Dimensions of Quality in Higher Education: Some Insights into Quality-based Performance Measurement. Retrieved form the World Wide Web. May 12, 2015.

20Sandru, Ioana Maria Diana. 2008. Dimensions of Quality in Higher Education: Some Insights into Quality-based Performance Measurement. Retrieved form the World Wide Web. May 12, 2015.

21Suskie, Linda. 2015

22Ibid. 31-32.

23Shray Vickie. Assuring Quality in Higher Education: Recommendations for Improving Accreditation. https://www2.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/hiedfuture/reports/schray2.pdf

24Ibid

25Ibid, 2.

26Ibid. 3

27Shray, 3.